Dr. Ben Thuy

“Palaeontology has always felt like a treasure hunt to me: you dig for unknown creatures, explore extinct worlds and try to understand the big changes in the world over the course of Earth’s history. Out of the whole range of possible research topics, I chose brittle stars and their fossil record as my main focus. Brittle stars are marine invertebrates related to starfish. They have an extensive but hitherto understudied fossil record, which makes them the perfect playground for exciting discoveries and exploration of further-reaching research questions, such as the origin of the deep-sea fauna. I have named several fossil brittle stars after my favourite bands and musicians from the metal and prog rock scenes to celebrate the hidden love between palaeontology and rock music. Both fields love to question the superficial self-image of our existence and both cultivate a deep enthusiasm for the extreme, the complex, the unconventional and of course the underground. Finally, there is a very personal reason: I myself am a drummer in a metal band and experience again and again that a successful concert and the exploration of unknown worlds trigger the same feeling of unleashed enthusiasm coupled with deep satisfaction. With the metal and prog rock fossil names, I can unite both passions.”

Gregory D. Edgecombe

“My research is split between studies of fossils and living animals, and is further split between studies using morphology and using DNA sequence data. My paleontological work mostly involves the early evolution of arthropods and other animals that first appeared in the fossil record in the Cambrian explosion around 542 million years ago, and my work on living animals mostly focuses on the evolution and taxonomy of centipedes. I was born and grew up in Canada, where I did my early studies in palaeontology. My first published research was on Silurian (about 430 million years ago) trilobites from northern Canada, and most of the species named for musicians came from that work. I did my PhD at Columbia University in New York City, where I trained with Niles Eldredge at the American Museum of Natural History and became interested in methods for inferring phylogenetic trees. After that I spent 14 years in the Australian Museum in Sydney concentrating on the systematics and interrelationships of Australian, and other southern hemisphere centipedes. The recurring theme of my research is integrating data from anatomy, molecular sequences and the fossil record to infer how the major groups of arthropods (insects, millipedes, crustaceans, arachnids) are interrelated. This is a considerable challenge because arthropods represent about 80% of living animal species diversity and have a prolific fossil history over 520 million years. Apart from being a palaeontologist I am also a bass player. Previously, I choose to name new species after members of my favourite bands like AC/DC, The Ramones and The Sex Pistols, because it seemed like a logical way to collectively name a group of related forms (e.g., four species in a genus, four members in a band) and because I figured it might mildly annoy my older colleagues. I am now myself middle-aged, and though I still play the same Fender bass, I now use sober species names.”

Jingmai O’Connor

“With my research, I seek to understand the origin of birds, which we can now say with great certainty, is within Dinosauria. I live and work in China, which is the 21st century Mecca of dinosaur paleontology. Within the past couple of decades, discoveries of Jurassic feathered dinosaurs and Early Cretaceous birds have revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur diversity and biology, but we still don’t understand which family of dinosaurs is most closely related to birds, how flight evolved, and other important questions. We are constantly finding new bizarre animals with bird-like characters or flying dinosaurs that aren’t birds – it’s a really exciting and dynamic field to work in. Thanks to my big brother I grew up listening to Bad Religion. At some point in graduate school, I got really into their music – I think the lyrics carry a very powerful message. Like most scientists, I have obsessive tendencies so, I did some research and found out that the lead singer Dr. Greg Graffin had done a Masters in Paleontology and PhD in Zoology, and had even volunteered at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County where I did my research. I immediately decided I wanted to name a species after him. The rate of discovery of new species in China is really high, and sometimes it’s hard to come up with good names for new taxa. However, convincing my more conservative Chinese co-authors to let me name a species after Greg Graffin from Bad Religion did take a few tries”.

Kari A. Prassack

“My research works to reconstruct the behaviors and interactions of extinct animals and to understand how ancient faunal communities functioned in response to environmental shifts. I focus on the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs (5.3 million years to 11,700 years ago) because they exhibit a mix of modern genera like Phalacrocorax (cormorant) and Lontra (otter) that co-existed with fantastical extinct beasts like giant ground sloths and saber-toothed cats. Most of my research has been on Pleistocene birds from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. So how did I end up describing a fossil otter? I was fortunate to end up working at Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument, which, with the addition of Lontra weiri, boasts nine fossil species of musteloid and at least ten other carnivoran taxa, including two that are currently being described. Lontra weiri is a small otter that represents the probable ancestor of North and South American river otters of the genus Lontra. Its species designation is a double etymology (two meanings). A weir is a bridge used to help capture fish. This fits well as the name for a piscivorous animal. Weir, however, is really used here in honor of guitarist Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead. Before I became a paleontologist, I followed my favorite band around the country. I attribute my sense of adventure to those days of living out of a backpack and travelling from state to state, dancing my nights away with thousands of other deadheads. Following the Grateful Dead fueled my sense of adventure and inspired me to follow my other passion: paleontology.”

Lea D. Numberger-Thuy

“The beauty and fascinating strategies of invertebrate life have struck me since my early years; as a curious and tenacious child, my way into science was predestined. Some years later, I found myself digging the ground and the drill cores for precious microfossils, always with some good and energizing tunes in my earphones. My initial scientific interests focused on foraminifera as climate archives. At some point, it turned out that my deepsea mud samples not only yielded foraminifera but also tiny bits and pieces of starfish, sea-urchins and their relatives. This literally opened Pandora’s box, producing loads of previously unknown species and unlocking echinoderms as deep-sea biodiversity model organisms.

When you pick and study microfossils you basically need three things: fine motor skills, coffee and good music. The tunes accompanying long hours in front of my PC during day and night shifts became part of me to the bone. Some songs are furthermore bound to specific memories from field trips or research vessel cruises.

My scientific life, I have to confess, has a soundtrack. Therefore, I decided to honor the most influential artists and groups, to thank them for helping me happily survive all the editing, submissions, deadlines and exams.”

Mats E. Eriksson

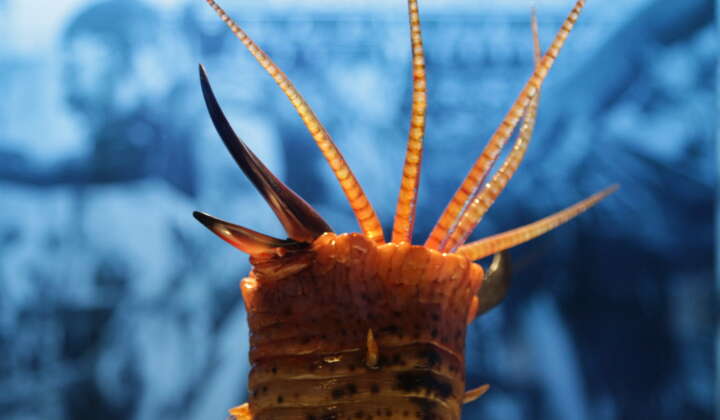

“My research is mainly focused on early Paleozoic biotas (541 – 416 million years ago) and their relationships to prehistoric environmental changes. This time interval embraces some of the most significant evolutionary events in Earth history, setting the agenda for life as we know it.I work chiefly as a micropaleontologist and our ‘tools of the trade’ comprise fossils in the microscopic size range that are extracted from their enclosing rocks in great abundance. Subsequently these fossils are studied to help us describe and understand the ancient ecosystems.

One of my favorite research interests concern the early fossil record of polychaete annelid worms. Like in modern-day oceans, these animals formed a significant part of the invertebrate faunas in past marine environments. Many polychaete worms are equipped with a complex jaw apparatus that is used for hunting and digging in the sea floor. The body of these worms consists mainly of soft tissue that very rarely fossilize, but their jaws (known as scolecodonts) are very resistant and can be found in great abundance as fossils. Although they are only up to a few millimeters in size, they differ significantly from species to species and allow very detailed analyses. Yet in spite of their great abundance and diversity in the geologic record, this group of fossils is not very well known compared to many other groups of fossils. However, on the positive side, this opens up possibilities for a wide array of research topics to be explored and new discoveries to be made, including the description and naming of taxa that are new to science.

Nomenclature is the science of naming organisms and of utmost importance to the fields of biology and palaeontology. Albeit nomenclature is usually a rather dull field I admit, it actually offers possibilities of creativity and amusement. In the case of Kalloprion kilmisteri and Kingnites diamondi I had the delightful opportunity of combining two of my biggest passions in life; palaeontology and heavy metal.

It was an easy decision when it came to naming these long-extinct polychaete worms to honor two legendary musicians; the Godfather of Rock’n’Roll, Lemmy Kilmister of Motörhead, and Danish metal maestro King Diamond. So, in addition to their obvious place in the history of heavy metal music, they now also have left an eternal imprint in science.”

Esben Horn

“When the exhibition “Rock Fossils on Tour” opened at Geomuseum Faxe in 2013, it consisted of two models and a handful of posters. I love heavy metal, and I love making paleontological reconstructions, so it made sense to make this little exhibition. One of the models portrayed the Silurian bristle worm Kingnites diamondi. King Diamond happened to show up at the exhibition’s opening as he was going to play at Copenhell the day after. The story was all over social media. What should have been a small one-off gig just kept going from one museum to the next. Each new gig had a new model, and the exhibition has now been travelling for nine years, and we are still counting …The combination of my passion for heavy metal music and model making has made Rock Fossils something special. In addition, I have been in contact with my idols in rock music and palaeontology. So, “Rock Fossils on Tour” represent Art’n’Science in its finest.”

Ursula Menkveld-Gfeller

“My research revolves around invertebrate fossils, with a focus on a more applied type of paleontology. Using large foraminifera as a basis, I am able to determine the age of rock sequences in the Alps. This method allows stratigraphic sequences not only to be dated but to be distinguished from one another when they are found in a disturbed state. Jurassic sea urchins have however also captured my attention in connection with the recent events. Inspired by the unusual “Rock Fossils” exhibition, it seemed only natural to name a newly discovered sea urchin species from the Jura Mountains after the Celtic metal band Eluveitie. This resonates in Eluveitie’s lyrics depicting the Switzerland’s Celtic era – even the name of the mountains and the geological period named after it are Celtic in origin, dating back to the name Jor. In other words, Switzerland’s cultural roots run deep, all the way back into geological history!”

Dr. Peter Jäger

“Since I am five years old, I am interested in spiders. From spider observing via keeping and breeding local and exotic spiders I got to biological sciences. My research travels in Asia unearth always undescribed species. So far, I described more than 400 new spider species, mainly huntsman spiders. When naming new species, a scientist can let his imagination run wild, of course only within the framework of nomenclatural rules. By the names I try to point to drawbacks in natural habitats. Heteropoda davidbowie, for instance, was accompanied by a message that forests in Southeast Asia are destroyed irretrievably in favour of palm oil plantations. In the same publication I named species for Nina Hagen and Udo Lindenberg. One spider genus in Madagascar I dedicated to Greta Thunberg with species names: Thunberga greta, Thunberga malala and Thunberga boyanslat. By honouring these young and promising planet citizens I express my hope for a better future.”